(Primitive Road by Bernadette Mayer)

Films

Ausweg [A Way] (2005, Germany, 14 min) dir. Harun Farocki

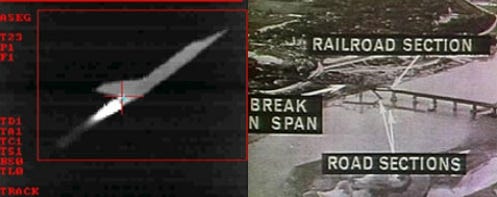

Farocki knows better than most that in our industrial-military age, creation itself becomes an act of destruction. Maybe more crucially though, that (technological) production is what sits between the two. Released in 2005, he was far ahead of the curve, and really it all comes down to this eviscerating quote: "Civil engineering has surpassed military engineering. A camera can distinguish a door from a junction. A bomb cannot distinguish between a factory and a kindergarten." War always finds a way.

Emma Mae (1976, United States, 100 min) dir. Jamaa Fanaka

Jamaa Fanaka’s film was made as part of the LA Rebellion wave of black American and diasporic filmmakers of the late 60s to 80s, something which will come as a bit of a surprise at first: unlike Charles Burnett or Halle Gerima, high artistic influences and socio-political stakes aren’t immediately detectable in Fanaka’s film. Instead, it seems like far more standard blaxploitation fare, a genre film which has its resonances in popular cinema rather than neorealism. But it’s too easy to counterpose arthouse and genre cinema against each other, when Fanaka demonstrates exactly how they might converge. Emma Mae —originally marketed with the more sensational title Black Sister’s Revenge— subverts and parodies the same blaxploitation aesthetics that it utilizes, making for one of the more radical critiques of the carceral state on film. The film follows the titluar Emma Mae, who comes up from the south to stay with her family in Los Angeles, much to the chagrin of her cousins who see her as a hick. Hoping not to have to babysit her at a social function with some peers, they set her up with Jessie, a hopeless drunk and show-off. When Jessie gets arrested along with his friend Zeke for beating up a police officer and evading arrest, Emma Mae makes it her mission to secure the money for his bail, turning herself against the entire system in the process.

This is where Fanaka’s film takes a radical turn. Organizing other students, Emma Mae’s bid to raise money via a car wash is ruined when the white owner informs her that the police have told them she can’t use his facilities anymore: “Those people up there look down here and they see one little black country girl organizing a bunch of kids, that society, with all their money and their brains, said there was no saving. You scare them Emma. You scare them because you embarass them.” This leads her to hatch up a plan to rob a bank, the logical conclusion for a group which has been denied every polite path to money or freedom.

The saving grace of Fanaka’s film is absolutely Jerri Hayes’ performance as Emma Mae, achingly realized across a landscape where she is spurned not just by white society, but by men who disregard her and take her for granted. The decision to rob the bank is met with some hesitation by her (male) comrades, who see a risk in that level of action. It’s at this point that Big Daddy (Malik Carter) steps in to back her up. Up until this point in the film, Big Daddy is mostly played for comic relief, shown as a caricature of the most paranoid and conspiratorial elements of macho black nationalism; the monolouge he delivers in defense of Emma Mae betrays this image, revealing an honest and tender man who has a clear vision of what’s at stake. “Y’all always jiving with me about my mumbling… see what you don’t know is that I mumble to forget. When I mumble I forget that I'm ashamed to be as old as I am and still walking around.” he lets out, “But y’all listen to me, and listen to that little lady over there, because what she’s trying to tell you, you at least stand a chance to get something out of. That is besides laughing, and bragging, about how many brothers you done shot and killed in some fool gang war. Now sit your funky asses down, and listen to a real woman for a change.” This impassioned delivery leads the group to succesfully expropriate the wealth of the bank to free Jessie and Zeke. Upon his release, Jessie proves to have used Emma Mae out of convenience this whole time, immediately cheating on her with another woman. The next day she goes to find him, both furious and forlorn, and after confronting him and receiving no sympathy, beats Jessie senseless. Emma Mae finds herself in a cruel world as she yells out to their community: “This is the nothing we’ve been looking up to! Just look at him with his old ass… still running around and talking about gang wars… this city ain’t nothing if you don’t know how to use it.” She walks off and returns to her family, perhaps disillusioned with the very same city that once held so much promise. The hollowness of what she finds everybody stuck in there, gang wars, drugs, empty cycles of promise and harm, suggests not even Emma Mae is exactly sure how to use the city.

Children Drawing Rainbows (1980, Japan, 85 min) dir. Mariko Miyagi

It’s hard to find any information online about Miyagi’s documentary, which centers on a school for disabled Japanese children. It was originally distributed by Art Theater Guild, the same organization that began as distributor of foreign films in Japan, but which quickly began to produce for Japanese avant-garde filmmakers, the likes of which included figures such as Toshio Matsumoto (Funeral Parade of Roses) and Shuji Terayama (Emperor Tomato Ketchup, Pastoral). Although it doesn’t appear to have been principally produced by ATG, it’s fitting that the film would be distributed by a group know for associations with films that were by equal turns experimental and documents of the society in which they were produced, for her film reflects both childlike fascination, as well as the role of imagination in creating beauty and care amidst darkness.

Mariko Miyagi, born Mariko Honme, began her career as a singer and actress from Tokyo. After playing the role of a child with cebreal palsy on stage, Miyagi was inspired to establish Nemunoki Gauken [Silktree], the arts oriented special needs school that her film focuses on. She died in March 2020. Again, it remains hard to find English-language coverage of Miyagi’s life and art, but it appears she created a cycle of films (perhaps all for ATG) about the school: The Silk Tree Ballad in 1974, Mother in 1977, and Children Drawing Rainbows in 1980. There also seems to be an hour-long anime special about Miyagi’s school called A Little Love Letter: Mariko and the Children of the Silk Tree that debuted in 1981, and which is described by one reference book as folllows: “divided into four seasonal chapters, the film uses highly realistic character designs based on the actual people involved.”

The film that Miyagi’s most immediately recalls for me is Iranian filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad’s 1963 documentary The House Is Black, which focuses on a leper colony in Iran. Like Miyagi, Farrokhzad doesn’t see disability as any kind of fundamental blemish of humanity, even as they both recognize the difficulties it brings for those living in an unjust world. But there’s also something about the role education as an alternate space can hold that emerges in both: even in the leper colony, young children are seen laughing together about nature and playtime in Farrokhzad’s film, while in Miyagi’s the children are free to express themselves however they see fit, communities coming together through education and art. The paintings and drawings that appear on screen are saccharine and beautiful, a reminder of the art that children make when they aren’t told to obsess over standards of craft, but rather to dwell in the act of creation itself. There’s also a sequence where a number of children appear to perform in an impromptu rock band, banging on drums and other instruments. The film ends with Miyagi running and pushing one student who stretches his arms out as if he were flying, a moment of joy perfectly captured.

Reading

Books I’ve finished since last writing:

Surveys (2016) by Natasha Stagg

Novel of the internet.

Utopia’s Debris (2008) and I Can Give You Anything But Love (2015) by Gary Indiana

Indiana is first and foremost a prose-stylist of a seemingly dying breed. Endlessly erudite and scathing, this book collects a series of essays representing his criticism from 1996 to 2008. He calls the quintipartite collection a “fugue,” a mode which can properly be appreciated ten years on, in a moment that feels like the soft decline of empire that he captures is only becoming louder and more ugly; in fact, the conditions that produced a critic like Indiana feel increasingly out of reach. I often consider Indiana’s pessimistic sentiments— his quip that “the few authentically educated, earnest people in the art world wake up contemplating suicide five mornings a week,” comes to mind, for one— as a kind of litmus test for whose criticism is worth reading. Which isn’t to say that we need to constantly be polemical or fatalistic, or that we can’t genuinely enjoy things, but rather that I trust someone who despairs about the state of art a lot more than a Jerry Saltz, who views the whole affair in a rather panglossian way and who never has, and never will, consider the material effects of history or the tragic confrontations that art, in its best moments, asks us to take. In his essay on Barbara Kruger, Indiana laments this kind of turn away from serious consideration, wryly observing the follies of such a viewpoint: “They’d like a New Yorker cartoon instead. And of course there will always be times when a New Yorker cartoon is more welcome than something darker and smarter.”

It’s the dark and the smart that he excels at dwelling in, and maybe also the abject. His preface sums up the cultural coordinates of his project quite well, if grimly so:

We live in the wreckage of a century I lived through the second half of, a century of false messiahs, twisted ideologies, shipwrecked hopes, pathetic answers. That the debris has implacably dogged us into the 21st century, with its increasingly hollow civic life, its disposable cultures, its massacres and genocides, its magnification of pathologies that no calendrical change can possibly detach from the human situation seems “par for the course,” and while abandoning the promiscuous use of the phrase “the incurable in human nature,” I have not yet found a more agreeable substitute for it.

I Can Give You Anything But Love is his memoir, and touches upon much of this in a more personal register. Covering his New England childhood and the current public sex culture in Havana— and crossing to 70s Los Angeles and San Francisco in between— it shows a very different, and very entertaining side of Indiana. That we often look for love where only sex is, or sex where only love is, seems to be what he obsesses over in between his youth and elderly life.

The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (2014) by Jennifer Nash

Nash perceives the archive of Black Feminism— as embodied by the writings of thinkers such as Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberlee Crenshaw, bell hooks, and Hortense Spillers— to be dominated by ideas of injury. Her book is a loving response which seeks to move past injury, and locate how the link between pornography and injury has also been one of pleasure for the subjects that both her and these other thinkers are concerned with, namely black women. It’s powerful, sometimes heady, and mostly takes the form of close reading coupled with historical context for something that I had no real context for (the racial nature of mid-to-late 20th century American pornography). A good read for anyone interested in gender, race, and critical studies of adult entertainment, as well as the multiple meanings the latter always contains.

Nog (1968) by Rudolph Wurlitzer

A novel about a man who travels across the country with an octopus. Has the same flair as Philip K. Dick novels, where the writing style seems to mimic the effect of a bad acid trip, and the prose style follows suit: both alluring and overwhelming.

Amulet (2002) by Robert Bolaño

I read a few of Bolaño’s novels last winter, and it was very pleasant to return to him in the form of this novella, which is more or less an extended prose poem. Some plotlines emerge concerning policemen, a hunchback, and a young writer, but the story remains mostly abstract and gives off a fun neo-noir feeling as a result. Perfect for reading across a few hazy afternoons.

Avidly Reads Theory (2019) by Jordan Alexander Stein

A sweet little book about how theory relates to life in a number of ironic and sincere ways; conjures kind of exactly what I imagine studying “theory” in the 90s was like for people both smart and funny.

Left Hemisphere: Mapping Critical Theory Today (2014) by Razmig Keuchyan

Good survey of current critical theory and the relationship it has to the tactics and circumstances of social movements.

Sexual Hegemony (2020) by Christopher Chitty

Truly essential reading for anyone interested in queer theory— really brilliant Marxist history of the relationship between sodomy, surplus populations and the state at the turn between feudalism and capitalism. Also has a robust theoretical apparatus which takes the best of Foucault and queer theory while returning political commitements to the table. A lot of people have written better about this than I ever will, there’s so much going on in it it’s hard to even know how to summarize it in a useful way. The rare piece of writing that actually changed how I think about a number of things related to history and sexuality that I’ve long taken for granted. Probably the most important book I read in 2020.

Campus Sex, Campus Security (2015) by Jennifer Doyle

Pithy, brilliant condemnation of the university and its complicity in the worst effects of neoliberalism, caught in the dialectic of a space that is both “outside” the “real world,” while also always-already under threat. “It’s an inversion. A wormhole. The campus is a ‘hunting ground’ and a private zone that must be protected from the ‘non-affiliate,’ from public invasion.” Made me curious about what abolitionist responses look like in practice, because of how absent they appear in possibility at present.